Introduction

For more than a century, Albert Einstein and his General Theory of Relativity (GR) have shaped the way we think about gravity and the cosmos. Thanks to this framework, we can predict the motion of planets, study black holes, and even detect gravitational waves.

But there is also a new perspective – TPK (Khandro Field Theory) – which interprets the same phenomena in a different and more direct way.

Einstein: Spacetime as a Stage

In Einstein’s view:

- Gravity is not a force, but the curvature of spacetime.

- Planets, photons, and particles move along “geodesics” – the straightest possible paths in this curved geometry.

- Effects like the bending of starlight near the Sun or gravitational time dilation come directly from this curvature.

It is an elegant but highly abstract framework: motion is dictated by the geometry of space and time itself.

TPK: The Field Instead of Geometry

TPK offers another picture:

- The foundation is not curved spacetime but a real physical field – the Khandro Field.

- This field has density and structure, and particles (including photons) respond to its gradients.

- The elevator, rocket, or planet is simply a system moving through this field. Their motion does not change the photon’s path – the field does.

In practice:

- Where Einstein speaks of “spacetime curvature,” TPK speaks of a physical medium/field.

- The trajectory of a photon depends only on the field, not on the motion of the observer.

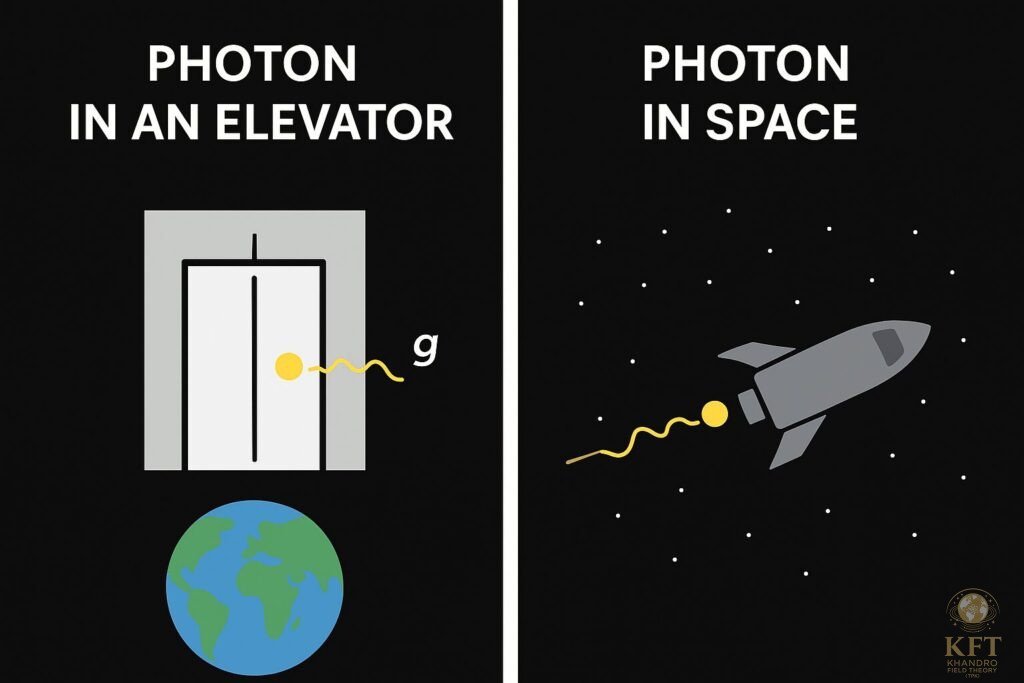

Key Difference: A Photon in the Elevator

- Einstein’s view: A photon in an accelerating elevator appears to curve toward the floor – an effect equivalent to gravity.

- TPK’s view: The photon does not “follow the elevator.” Its path is determined only by the Khandro Field. The elevator is merely a moving measurement frame, with no influence on the photon’s trajectory.

Agreement with Observations

Both GR and TPK predict:

- bending of light near massive bodies,

- time dilation in gravitational fields,

- extreme phenomena like black holes.

The difference lies in interpretation:

- Einstein – gravity as curved geometry,

- TPK – gravity as the dynamics of a physical field.

Conclusion

History shows that great ideas can be described in different languages.

Einstein gave gravity the language of geometry, while TPK gives it the language of a field.

Both fit observations – but TPK offers a more intuitive, physical picture: light and matter always follow the field, not the observer’s motion.